Project Mercury

Retroactive logo designed from 1964 Mercury Seven astronaut memorial |

| Country of origin |

United States |

| Responsible organization |

NASA |

| Purpose |

Manned Earth orbital flight |

| Status |

completed |

| Program history |

| Cost |

$277 million (1965)[1] |

| Program duration |

1958–1963 |

| First flight |

September 9, 1959 |

| First crewed flight |

May 5, 1961 |

| Last flight |

May 15–16, 1963 |

| Successes |

11 |

| Failures |

3

|

| Partial failures |

1: Big Joe 1 |

| Launch site(s) |

|

| Vehicle information |

| Vehicle type |

capsule |

| Crew vehicle |

Mercury |

| Crew capacity |

1 |

| Launch vehicle(s) |

|

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Union. Taken over from the U.S. Air Force by the newly created civilian space agency NASA, it conducted twenty unmanned developmental flights (some using animals), and six successful flights by astronauts. The program, which took its name from the god of travel in Roman mythology, cost $277 million in 1965 US dollars, and involved the work of 2 million people.[1] The astronauts were collectively known as the “Mercury Seven“, and each spacecraft was given a name ending with a “7” by its pilot.

The Space Race began with the 1957 launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik 1. This came as a shock to the American public, and led to the creation of NASA to expedite existing U.S. space exploration efforts, and place most of them under civilian control. After the successful launch of the Explorer 1 satellite in 1958, manned spaceflight became the next goal. The Soviet Union put the first human, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, into a single orbit aboard Vostok 1 on April 12, 1961. Shortly after this, on May 5, the U.S. launched its first astronaut, Alan Shepard, on a suborbital flight. Soviet Gherman Titov followed with a day-long orbital flight in August, 1961. The U.S. reached its orbital goal on February 20, 1962, when John Glenn made three orbits around the Earth. When Mercury ended in May 1963, both nations had sent six people into space, but the Soviets led the U.S. in total time spent in space.

The Mercury space capsule was produced by McDonnell Aircraft, and carried supplies of water, food and oxygen for about one day in a pressurized cabin. Mercury flights were launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, on launch vehicles modified from the Redstone and Atlas D missiles. The capsule was fitted with a launch escape rocket to carry it safely away from the launch vehicle in case of a failure. The flight was designed to be controlled from the ground via the Manned Space Flight Network, a system of tracking and communications stations; back-up controls were outfitted on board. Small retrorockets were used to bring the spacecraft out of its orbit, after which an ablative heat shield protected it from the heat of atmospheric reentry. Finally, a parachute slowed the craft for a water landing. Both astronaut and capsule were recovered by helicopters deployed from a U.S. Navy ship.

After a slow start riddled with humiliating mistakes, the Mercury project gained popularity, its missions followed by millions on radio and TV around the world. Its success laid the groundwork for Project Gemini, which carried two astronauts in each capsule and perfected space docking maneuvers essential for manned lunar landings in the subsequent Apollo program announced a few weeks after the first manned Mercury flight.

Creation[edit]

Project Mercury was officially approved on October 7, 1958 and publicly announced on December 17.[3] Originally called Project Astronaut, President Dwight Eisenhower felt that gave too much attention to the pilot. Instead, the name Mercury was chosen from classical mythology, which had already lent names to rockets like the Greek Atlas and Roman Jupiter for the SM-65 and PGM-19 missiles.[3] It absorbed military projects with the same aim, such as the Air Force Man In Space Soonest.[5][n 1]

Background[edit]

Following the end of World War II, a nuclear arms race evolved between the U.S. and the Soviet Union (USSR). Since the USSR did not have a large fleet of bomber planes to deliver such weapons to the U.S., or bases in the western hemisphere from which to deploy them, Joseph Stalin decided to develop intercontinental ballistic missiles, which drove a missile race. The rocket technology in turn enabled both sides to develop Earth-orbiting satellites for communications, and gathering weather data and intelligence. Americans were shocked when the Soviet Union placed the first satellite into orbit in October 1957, leading to a growing fear that the U.S. was falling into a “missile gap“.[9] A month later, the Soviets launched Sputnik 2, carrying a dog into orbit. Though the animal was not recovered alive, it was obvious their goal was manned spaceflight. Unable to disclose details of military space projects, President Eisenhower ordered the creation of a civilian space agency in charge of civilian and scientific space exploration. Based on the federal research agency National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), it was named the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.[11] It achieved its first goal, an American satellite in space, in 1958. The next goal was to put a man there.

The limit of space was defined at the time as a minimum altitude of 62 mi (100 km), and the only way to reach it was by using rocket powered boosters.[14] This created risks for the pilot, including explosion, high g-forces and vibrations during lift off through a dense atmosphere,[15] and temperatures of more than 10,000 °F (5,500 °C) from air compression during reentry.[16]

In space, pilots would require pressurized chambers or space suits to supply fresh air. While there, they would experience weightlessness, which could potentially cause disorientation.[18] Further potential risks included radiation and micrometeoroid strikes, both of which would normally be absorbed in the atmosphere.[19] All seemed possible to overcome: experience from satellites suggested micrometeoroid risk was negligible,[20] and experiments in the early 1950s with simulated weightlessness, high g-forces on humans, and sending animals to the limit of space, all suggested potential problems could be overcome by known technologies.[21] Finally, reentry was studied using the nuclear warheads of ballistic missiles,[22] which demonstrated a blunt, forward-facing heat shield could solve the problem of heating.[22]

Organization[edit]

T. Keith Glennan had been appointed the first Administrator of NASA, with Hugh L. Dryden (last Director of NACA) as his Deputy, at the creation of the agency on October 1, 1958.[23] Glennan would report to the president through the National Aeronautics and Space Council. The group responsible for Project Mercury was NASA’s Space Task Group, and the goals of the program were to orbit a manned spacecraft around Earth, investigate the pilot’s ability to function in space, and to recover both pilot and spacecraft safely.[25] Existing technology and off-the-shelf equipment would be used wherever practical, the simplest and most reliable approach to system design would be followed, and an existing launch vehicle would be employed, together with a progressive test program.[26] Spacecraft requirements included: a launch escape system to separate the spacecraft and its occupant from the launch vehicle in case of impending failure; attitude control for orientation of the spacecraft in orbit; a retrorocket system to bring the spacecraft out of orbit; drag braking blunt body for atmospheric reentry; and landing on water.[26] To communicate with the spacecraft during an orbital mission, an extensive communications network had to be built.[27] In keeping with his desire to keep from giving the U.S. space program an overly military flavor, President Eisenhower at first hesitated to give the project top national priority (DX rating under the Defense Production Act), which meant that Mercury had to wait in line behind military projects for materials; however, this rating was granted in May 1959.

Contractors and facilities[edit]

Twelve companies bid to build the Mercury spacecraft on a $20 million ($163 million adjusted for inflation) contract.[29] In January 1959, McDonnell Aircraft Corporation was chosen to be prime contractor for the spacecraft.[30] Two weeks earlier, North American Aviation, based in Los Angeles, was awarded a contract for Little Joe, a small rocket to be used for development of the launch escape system.[31][n 2] The World Wide Tracking Network for communication between the ground and spacecraft during a flight was awarded to the Western Electric Company.[32] Redstone rockets for suborbital launches were manufactured in Huntsville, Alabama by the Chrysler Corporation[33] and Atlas rockets by Convair in San Diego, California. For manned launches, the Atlantic Missile Range at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida was made available by the USAF. This was also the site of the Mercury Control Center while the computing center of the communication network was in Goddard Space Center, Maryland. Little Joe rockets were launched from Wallops Island, Virginia.[37] Astronaut training took place at Langley Research Center in Virginia, Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio, and Naval Air Development Center Johnsville in Warminster, PA. Langley wind tunnels[39] together with a rocket sled track at Holloman Air Force Base at Alamogordo, New Mexico were used for aerodynamic studies. Both Navy and Air Force aircraft were made available for the development of the spacecraft’s landing system, and Navy ships and Navy and Marine Corps helicopters were made available for recovery.[n 3] South of Cape Canaveral the town of Cocoa Beach boomed.[43]From here, 75,000 people watched the first American orbital flight being launched in 1962.[43]

-

Wallops Island test facility, 1961

-

Mercury Control Center, Cape Canaveral, 1963

-

Location of production and operational facilities of Project Mercury

Spacecraft[edit]

The Mercury spacecraft’s principal designer was Maxime Faget, who started research for manned spaceflight during the time of the NACA. It was 10.8 feet (3.3 m) long and 6.0 feet (1.8 m) wide; with the launch escape system added, the overall length was 25.9 feet (7.9 m). With 100 cubic feet (2.8 m3) of habitable volume, the capsule was just large enough for a single crew member.[46] Inside were 120 controls: 55 electrical switches, 30 fuses and 35 mechanical levers.[47] The heaviest spacecraft, Mercury-Atlas 9, weighed 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) fully loaded.[48] Its outer skin was made of René 41, a nickel alloy able to withstand high temperatures.

The spacecraft was cone shaped, with a neck at the narrow end. It had a convex base, which carried a heat shield (Item 2 in the diagram below) consisting of an aluminum honeycomb covered with multiple layers of fiberglass.[51] Strapped to it was a retropack (1) consisting of three rockets deployed to brake the spacecraft during reentry. Between these were three minor rockets for separating the spacecraft from the launch vehicle at orbital insertion.[54] The straps that held the package could be severed when it was no longer needed. Next to the heat shield was the pressurized crew compartment (3). Inside an astronaut would be strapped to a form-fitting seat, with instruments in front and his back to the heat shield. Underneath the seat was the environmental control system supplying oxygen and heat, scrubbing the air of CO2, vapor and odors, and (on orbital flights) collecting urine.[n 4] The recovery compartment (4) at the narrow end of the spacecraft contained three parachutes: a drogue to stabilize free fall and two main chutes, a primary and reserve. Between the heat shield and inner wall of the crew compartment was a landing skirt, deployed by letting down the heat shield before landing. On top of the recovery compartment was the antenna section (5) containing both antennas for communication and scanners for guiding spacecraft orientation. Attached was a flap used to ensure the spacecraft was faced heat shield first during reentry.[66]A launch escape system (6) was mounted to the narrow end of the spacecraft containing three small solid-fueled rockets which could be fired briefly in a launch failure to separate the capsule safely from its booster. It would deploy the capsule’s parachute for a landing nearby at sea. (See also Mission profile for details.)

The Mercury spacecraft did not have an on-board computer, instead relying on all computation for re-entry to be calculated by computers on the ground, with their results (retrofire times and firing attitude) then transmitted to the spacecraft by radio while in flight.[69][70] All computer systems used in the Mercury space program were housed in NASA facilities on Earth.[69] The computer systems were IBM 701 computers.[71][72](See also Ground control for details.)

-

1. Retropack. 2. Heatshield. 3. Crew compartment. 4. Recovery compartment. 5. Antenna section. 6. Launch escape system.

-

Retropack: Retrorockets with red posigrade rockets

-

Landing skirt deployment: on release the skirt is filled with air; on impact the air is pressed out again

Pilot accommodations[edit]

John Glenn wearing his Mercury space suit

The astronaut lay in a sitting position with his back to the heat shield, which was found to be the position that best enabled a human to withstand the high g-forces of launch and re-entry. A form-fitted fiberglass seat was custom-molded from each astronaut’s space-suited body for maximum support. Near his left hand was a manual abort handle to activate the launch escape system if necessary prior to or during liftoff, in case the automatic trigger failed.

To supplement the onboard environmental control system, he wore a pressure suit with its own oxygen supply, which would also cool him. A cabin atmosphere of pure oxygen at a low pressure of 5.5 psi (equivalent to an altitude of 24,800 feet (7,600 m)) was chosen, rather than one with the same composition as air (nitrogen/oxygen) at sea level.[75] This was easier to control, avoided the risk of decompression sickness (known as “the bends”),[n 5] and also saved on spacecraft weight. Fires (which never occurred) would have to be extinguished by emptying the cabin of oxygen. In such case, or failure of the cabin pressure for any reason, the astronaut could make an emergency return to Earth, relying on his suit for survival.[78]The astronauts normally flew with their visor up, which meant that the suit was not inflated. With the visor down and the suit inflated, the astronaut could only reach the side and bottom panels, where vital buttons and handles were placed.[79]

The astronaut also wore electrodes on his chest to record his heart rhythm, a cuff that could take his blood pressure, and a rectal thermometer to record his temperature (this was replaced by an oral thermometer on the last flight). Data from these was sent to the ground during the flight. The astronaut normally drank water and ate food pellets.[n 6]

Once in orbit, the spacecraft could be rotated in three directions: along its longitudinal axis (roll), left to right from the astronaut’s point of view (yaw), and up or down (pitch). Movement was created by rocket-propelled thrusters which used hydrogen peroxide as a fuel.[83] For orientation, the pilot could look through the window in front of him or from a screen connected to a periscope which could be turned 360°.

The Mercury astronauts had taken part in the development of their spacecraft, and insisted that manual control, and a window, be elements of its design. As a result, spacecraft movement and other functions could be controlled three ways: remotely from the ground when passing over a ground station, automatically guided by onboard instruments, or manually by the astronaut, who could replace or override the two other methods. Experience validated the astronauts’ insistence on manual controls. Without them, Gordon Cooper’s manual reentry during the last flight would not have been possible.[87]

Development and production[edit]

Spacecraft production in clean room at McDonnell Aircraft, St. Louis

The Mercury spacecraft design was modified three times by NASA between 1958 and 1959. After bidding by potential contractors had been completed, NASA selected the design submitted as “C” in November 1958. After it failed a test flight in July 1959, a final configuration, “D”, emerged. The heat shield shape had been developed earlier in the 1950s through experiments with ballistic missiles, which had shown a blunt profile would create a shock wave that would lead most of the heat around the spacecraft. To further protect against heat, either a heat sink, or an ablative material, could be added to the shield.[92] The heat sink would remove heat by the flow of the air inside the shock wave, whereas the ablative heat shield would remove heat by a controlled evaporation of the ablative material.[93] After unmanned tests, the latter was chosen for manned flights.[94] Apart from the capsule design, a rocket plane similar to the existing X-15 was considered.[95] This approach was still too far from being able to make a spaceflight, and was consequently dropped.[96][n 7] The heat shield and the stability of the spacecraft were tested in wind tunnels,[39] and later in flight. The launch escape system was developed through unmanned flights. During a period of problems with development of the landing parachutes, alternative landing systems such as the Rogallo glider wingwere considered, but ultimately scrapped.[102]

The spacecraft were produced at McDonnell Aircraft, St. Louis, Missouri in clean rooms and tested in vacuum chambers at the McDonnell plant. The spacecraft had close to 600 subcontractors, such as Garrett AiResearch which built the spacecraft’s environmental control system.[30] Final quality control and preparations of the spacecraft were made at Hangar S at Cape Canaveral.[n 8] NASA ordered 20 production spacecraft, numbered 1 through 20.[30] Five of the 20, Nos. 10, 12, 15, 17, and 19, were not flown.Spacecraft No. 3 and No. 4 were destroyed during unmanned test flights. Spacecraft No. 11 sank and was recovered from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean after 38 years. Some spacecraft were modified after initial production (refurbished after launch abort, modified for longer missions, etc.)[n 9] A number of Mercury boilerplate spacecraft(made from non-flight materials or lacking production spacecraft systems) were also made by NASA and McDonnell.[111] They were designed and used to test spacecraft recovery systems and the escape tower.[112] McDonnell also built the spacecraft simulators used by the astronauts during training.

-

Evolution of capsule design, 1958–59

-

Experiment with boilerplate spacecraft, 1959

Launch vehicles[edit]

Launch vehicles: 1. Mercury-Atlas (orbital flights). 2. Mercury-Redstone (suborbital flights). 3. Little Joe (unmanned tests)

Launch Escape System testing[edit]

A small launch vehicle (55 feet (17 m) long) called Little Joe was used for unmanned tests of the launch escape system, using a Mercury capsule with an escape tower mounted on it.[115] Its main purpose was to test the system at a point called max-q, at which air pressure against the spacecraft peaked, making separation of the launch vehicle and spacecraft most difficult. It was also the point at which the astronaut was subjected to the heaviest vibrations. The Little Joe rocket used solid-fuel propellant and was originally designed in 1958 by the NACA for suborbital manned flights, but was redesigned for Project Mercury to simulate an Atlas-D launch. It was produced by North American Aviation. It was not able to change direction, instead its flight depended on the angle from which it was launched. Its maximum altitude was 100 mi (160 km) fully loaded.[119] A Scout launch vehicle was used for a single flight intended to evaluate the tracking network; however, it failed and was destroyed from the ground shortly after launch.[120]

Suborbital flight[edit]

The Mercury-Redstone Launch Vehicle, an 83-foot (25 m) tall (with capsule and escape system) single-stage launch vehicle used for suborbital (ballistic) flights. It had a liquid-fueled engine that burned alcohol and liquid oxygen producing about 75,000 pounds of thrust, which was not enough for orbital missions. It was a descendant of the German V-2,[33] and developed for the U.S. Army during the early 1950s. It was modified for Project Mercury by removing the warhead and adding a collar for supporting the spacecraft together with material for damping vibrations during launch. Its rocket motor was produced by North American Aviation and its direction could be altered during flight by its fins. They worked in two ways: by directing the air around them, or by directing the thrust by their inner parts (or both at the same time).[33] Both the Atlas-D and Redstone launch vehicles contained an automatic abort sensing system which allowed them to abort a launch by firing the launch escape system if something went wrong. The Jupiter rocket, also developed by Von Braun’s team at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, was considered as well for intermediate Mercury suborbital flights at a higher speed and altitude than Redstone, but this plan was dropped when it turned out that man-rating Jupiter for the Mercury program would actually cost more than flying an Atlas due to scale of economics–Jupiter’s only use other than as a missile system was for the short-lived Juno II launch vehicle and keeping a full staff of technical personnel around solely to fly a few Mercury capsules would result in excessively high costs.[124]

Orbital flight[edit]

Orbital missions required use of the Atlas LV-3B, a man-rated version of the Atlas D which was originally developed as the United States first operational intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) by Convair for the Air Force during the mid-1950s.[127] The Atlas was a “one-and-one-half-stage” rocket fueled by kerosene and liquid oxygen (LOX). The rocket by itself stood 67 feet (20 m) high; total height of the Atlas-Mercury space vehicle at launch was 95 feet (29 m).

The Atlas first stage was a booster skirt with two engines burning liquid fuel.[n 10] This together with the larger sustainer second stage gave it sufficient power to launch a Mercury spacecraft into orbit. Both stages fired from lift-off with the thrust from the second stage sustainer engine passing through an opening in the first stage. After separation from the first stage, the sustainer stage continued alone. The sustainer also steered the rocket by thrusters guided by gyroscopes. Smaller vernier rockets were added on its sides for precise control of maneuvers.

Gallery[edit]

-

Little Joe assembling at Wallops Island

-

Unloading Atlas at Cape Canaveral

-

Atlas – with spacecraft mounted – on launch pad at Launch Complex 14

Astronauts[edit]

Left to right: Grissom, Shepard, Carpenter, Schirra, Slayton, Glenn and Cooper, 1962

NASA announced the selected seven astronauts – known as the Mercury Seven – on April 9, 1959,[131] they were:[132]

- LT (later CDR) Malcolm Scott Carpenter (1925–2013), USN

- Capt (later Col) Leroy Gordon “Gordo” Cooper, Jr. (1927–2004), USAF

- Maj (later Col) John Herschel Glenn, Jr. (1921–2016), USMC

- Capt (later Lt Col) Virgil Ivan “Gus” Grissom (1926–1967), USAF

- LCDR (later CAPT) Walter Marty “Wally” Schirra, Jr. (1923–2007), USN

- LCDR (later RADM) Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr. (1923–1998), USN

- Maj Donald Kent “Deke” Slayton (1924–1993), USAF

Shepard became the first American in space by making a suborbital flight in May 1961.[133] He went on to fly in the Apollo program and became the only Mercury astronaut to walk on the Moon. Gus Grissom, who became the second American in space, also participated in the Gemini and Apollo programs, but died in January 1967 during a pre-launch test for Apollo 1. Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth in February 1962, then quit NASA and went into politics, serving as a US Senator from 1974 to 1999, and returned to space in 1998 as a Payload Specialist aboard STS-95. Deke Slayton was grounded in 1962, but remained with NASA and was appointed Chief Astronaut at the beginning of Project Gemini. He remained in the position of senior astronaut, in charge of space crew flight assignments among many other responsibilities, until towards the end of Project Apollo, when he resigned and began training to fly on the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975, which he successfully did. Gordon Cooper became the last to fly in Mercury and made its longest flight, and also flew a Gemini mission. [138] Carpenter’s Mercury flight was his only trip into space. Schirra flew the third orbital Mercury mission, and then flew a Gemini mission. Three years later, he commanded the first manned Apollo mission, becoming the only person to fly in all three of those programs.

One of the astronauts’ tasks was publicity; they gave interviews to the press and visited project manufacturing facilities to speak with those who worked on Project Mercury. To make their travels easier, they requested and got jet fighters for personal use. The press was especially fond of John Glenn, who was considered the best speaker of the seven. They sold their personal stories to Life magazine which portrayed them as patriotic, God-fearing family men. Life was also allowed to be at home with the families while the astronauts were in space. During the project, Grissom, Carpenter, Cooper, Schirra and Slayton stayed with their families at or near Langley Air Force Base; Glenn lived at the base and visited his family in Washington DC on weekends. Shepard lived with his family at Naval Air Station Oceana in Virginia.

Other than Grissom, who was killed in the 1967 Apollo 1 fire, the other six survived past retirement and died between 1993 and 2016.

Selection and training[edit]

It was first envisaged that the pilot could be any man or woman willing to take a personal risk. However, the first Americans to venture into space were drawn, on President Eisenhower’s insistence, from a group of 508 active duty military test pilots,[145] who were either USN or USMC naval aviation pilots (NAPs), or USAF pilots of Senior or Command rating. This excluded women, since there were no female military test pilots at the time. It also excluded civilian NASA X-15 pilot Neil Armstrong, though he had been selected by the U.S. Air Force in 1958 for its Man In Space Soonest program, which was replaced by Mercury. Although Armstrong had been a combat-experienced NAP during the Korean War, he left active duty in 1952.[n 11] Armstrong became NASA’s first civilian astronaut in 1962 when he was selected for NASA’s second group,and became the first man on the Moon in 1969.

It was further stipulated that candidates should be between 25 and 40 years old, no taller than 5 ft 11 in (1.80 m), and hold a college degree in a STEM subject. The college degree requirement excluded the USAF’s X-1 pilot, then-Lt Col (later Brig Gen) Chuck Yeager, the first person to exceed the speed of sound. He later became a critic of the project, ridiculing especially the use of monkeys as test subjects.[n 12] USAF Capt (later Col) Joseph Kittinger, a USAF fighter pilot and stratosphere balloonist, met all the requirements but preferred to stay in his contemporary project. Other potential candidates declined because they did not believe that manned spaceflight had a future beyond Project Mercury.[n 13] From the original 508, 110 candidates were selected for an interview, and from the interviews, 32 were selected for further physical and mental testing. Their health, vision, and hearing were examined, together with their tolerance to noise, vibrations, g-forces, personal isolation, and heat.[155] In a special chamber, they were tested to see if they could perform their tasks under confusing conditions. The candidates had to answer more than 500 questions about themselves and describe what they saw in different images. Navy LT (later CAPT) Jim Lovell, a NAP who was later an astronaut in the Gemini and Apollo programs, did not pass the physical tests. After these tests it was intended to narrow the group down to six astronauts, but in the end it was decided to keep seven.

The astronauts went through a training program covering some of the same exercises that were used in their selection. They simulated the g-force profiles of launch and reentry in a centrifuge at the Naval Air Development Center, and were taught special breathing techniques necessary when subjected to more than 6 g. Weightlessness training took place in aircraft, first on the rear seat of a two-seater fighter and later inside converted and padded cargo aircraft. They practiced gaining control of a spinning spacecraft in a machine at the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory called the Multi-Axis Spin-Test Inertia Facility (MASTIF), by using an attitude controller handle simulating the one in the spacecraft.[158][159] A further measure for finding the right attitude in orbit was star and Earth recognition training in planetaria and simulators.Communication and flight procedures were practiced in flight simulators, first together with a single person assisting them and later with the Mission Control Center. Recovery was practiced in pools at Langley, and later at sea with frogmen and helicopter crews.[162]

-

-

Weightlessness simulation in a C-131

-

-

Flight trainer at Cape Canaveral

-

Mission profile[edit]

Suborbital[edit]

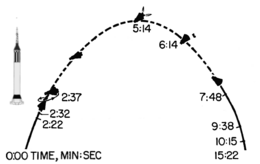

Profile. See timetable for explanation. Dashed line: region of weightlessness.

A Redstone rocket was used to boost the capsule for 2 minutes and 30 seconds to an altitude of 32 nautical miles (59 km) and let it continue on a ballistic curve after booster-spacecraft separation. The launch escape system was jettisoned at the same time. At the top of the curve, the spacecraft’s retrorockets were fired for testing purposes; they were not necessary for re-entry because orbital speed had not been attained. The spacecraft landed in the Atlantic Ocean. The suborbital mission took about 15 minutes, had an apogee altitude of 102–103 nautical miles (189–191 km), and a downrange distance of 262 nautical miles (485 km).[138] From the time of booster-spacecraft separation until reentry where air started to slow down the spacecraft, the pilot would experience weightlessness as shown on the image.[n 14] The recovery procedure would be the same as an orbital mission.

| [show]Timetable (min:sec.) |

Orbital[edit]

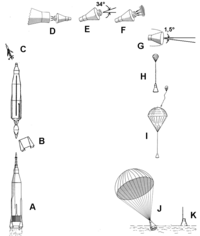

Profile. A-C: launch. D: insert into orbit. E-K: re-entry and landing

Preparations for a mission started a month in advance with the selection of the primary and back-up astronaut; they would practice together for the mission. For three days prior to launch, the astronaut went through a special diet to minimize his need for defecating during the flight. On the morning of the trip he typically ate a steak breakfast. After having sensors applied to his body and being dressed in the pressure suit, he started breathing pure oxygen to prepare him for the atmosphere of the spacecraft. He arrived at the launch pad, took the elevator up the launch tower and entered the spacecraft two hours before launch.[n 15] Once the astronaut was secured inside, the hatch was bolted, the launch area evacuated and the mobile tower rolled back. After this, the launch vehicle was filled with liquid oxygen. The entire procedure of preparing for launch and launching the spacecraft followed a time table called the countdown. It started a day in advance with a pre-count, in which all systems of the launch vehicle and spacecraft were checked. After that followed a 15-hour hold, during which pyrotechnics were installed. Then came the main countdown which for orbital flights started 6½ hours before launch (T – 390 min), counted backwards to launch (T = 0) and then forward until orbital insertion (T + 5 min).[n 16]

On an orbital mission, the Atlas’ rocket engines were ignited 4 seconds before lift-off. The launch vehicle was held to the ground by clamps and then released when sufficient thrust was built up at lift-off (A). After 30 seconds of flight, the point of maximum dynamic pressure against the vehicle was reached, at which the astronaut felt heavy vibrations.After 2 minutes and 10 seconds, the two outboard booster engines shut down and were released with the aft skirt, leaving the center sustainer engine running (B). At this point, the launch escape system was no longer needed, and was separated from the spacecraft by its jettison rocket (C).[n 17] The space vehicle moved gradually to a horizontal attitude until, at an altitude of 87 nautical miles (161 km), the sustainer engine shut down and the spacecraft was inserted into orbit (D). This happened after 5 minutes and 10 seconds in a direction pointing east, whereby the spacecraft would gain speed from the rotation of the Earth.[n 18] Here the spacecraft fired the three posigrade rockets for a second to separate it from the launch vehicle.[n 19] Just before orbital insertion and sustainer engine cutoff, g-loads peaked at 8 g (6 g for a suborbital flight). In orbit, the spacecraft automatically turned 180°, pointed the retropackage forward and its nose 14.5° downward and kept this attitude for the rest of the orbital phase of the mission, as it was necessary for communication with the ground.[182][n 20]

Once in orbit, it was not possible for the spacecraft to change its trajectory except by initiating reentry. Each orbit would typically take 88 minutes to complete. The lowest point of the orbit called perigee was at the point where the spacecraft entered orbit and was about 87 nautical miles (161 km), the highest called apogee was on the opposite side of Earth and was about 150 nautical miles (280 km). When leaving orbit (E) the angle downward was increased to 34°, which was the angle of retrofire.[182] Retrorockets fired for 10 seconds each (F) in a sequence where one started 5 seconds after the other. During reentry (G), the astronaut would experience about 8 g (11–12 g on a suborbital mission).[188] The temperature around the heat shield rose to 3,000 °F (1,600 °C) and at the same time, there was a two-minute radio blackout due to ionization of the air around the spacecraft. After re-entry, a small, drogue parachute (H) was deployed at 21,000 ft (6,400 m) for stabilizing the spacecraft’s descent. The main parachute (I) was deployed at 10,000 ft (3,000 m) starting with a narrow opening that opened fully in a few seconds to lessen the strain on the lines.[190] Just before hitting the water, the landing bag inflated from behind the heat shield to reduce the force of impact (J).[190] Upon landing the parachutes were released. An antenna (K) was raised and sent out signals that could be traced by ships and helicopters. Further, a green marker dye was spread around the spacecraft to make its location more visible from the air.[n 21] Frogmen brought in by helicopters inflated a collar around the craft to keep it upright in the water.[n 22] The recovery helicopter hooked onto the spacecraft and the astronaut blew the escape hatch to exit the capsule. He was then hoisted aboard the helicopter that finally brought both him and the spacecraft to the ship.[n 23]

-

John Glenn in orbit (Mercury-Atlas 6)

-

Friendship 7 in orbit (artist concept)

-

Recovery seen from helicopter (Mercury-Redstone 3)

Ground control[edit]

Inside Control Center at Cape Canaveral (Mercury-Atlas 8)

The number of personnel supporting a Mercury mission was typically around 18,000, with about 15,000 people associated with recovery.[193][n 24] Most of the others followed the spacecraft from the World Wide Tracking Network, a chain of 18 stations placed around the equator, which was based on a network used for satellites and made ready in 1960. It collected data from the spacecraft and provided two-way communication between the astronaut and the ground. Each station had a range of 700 nautical miles (1,300 km) and a pass typically lasted 7 minutes. Mercury astronauts on the ground would take part of the Capsule Communicator or CAPCOM who communicated with the astronaut in orbit.[199][200][n 25] Data from the spacecraft was sent to the ground, processed at the Goddard Space Center and relayed to the Mercury Control Center at Cape Canaveral. In the Control Center, the data was displayed on boards on each side of a world map, which showed the position of the spacecraft, its ground track and the place it could land in an emergency within the next 30 minutes.

The World Wide Tracking Network went on to serve subsequent space programs, until it was replaced by a satellite relay system in the 1980s Mission Control Center was moved from Cape Canaveral to Houston in 1965.

Flights[edit]

/

Cape Canaveral

Hawaii

Freedom 7

Liberty Bell 7

Friendship 7

Aurora 7

Sigma 7

Faith 7

On April 12, 1961 the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person in space on an orbital flight.[204] Alan Shepard became the first American in space on a suborbital flight three weeks later, on May 5, 1961.[133] John Glenn, the third Mercury astronaut to fly, became the first American to reach orbit on February 20, 1962, but only after the Soviets had launched a second cosmonaut, Gherman Titov, into a day-long flight in August 1961.[205] Three more Mercury orbital flights were made, ending on May 16, 1963 with a day-long, 22 orbit flight.[138] However, the Soviet Union ended its Vostok program the next month, with the human spaceflight endurance record set by the 82-orbit, almost 5-day Vostok 5 flight.

All of the 6 manned Mercury flights were successful though some intended flight were cancelled during the project (see below).[207] The main medical problems encountered were simple personal hygiene, and post-flight symptoms of low blood pressure.[193] The launch vehicles had been tested through unmanned flights, therefore the numbering of manned missions did not start with 1.[208] Also, since two different launch vehicles were used, there were two separate numbered series: MR for “Mercury-Redstone” (suborbital flights), and MA for “Mercury-Atlas” (orbital flights). These names were not popularly used, since the astronauts followed a pilot tradition, each giving their spacecraft a name. They selected names ending with a “7” to commemorate the seven astronauts.[132] Times given are Universal Coordinated Time, local time + 5 hours.

| Mission[n 26] |

Call-sign |

Pilot |

Launch time |

Launch site |

Duration |

Orbits |

Apogee

mi (km) |

Perigee

mi (km) |

Max. velocity

mph (km/h) |

Miss

mi (km) |

| Mercury-Redstone 3 |

Freedom 7 |

Shepard |

14:34 on May 5, 1961 |

Launch Complex-5 |

15 m 22 s |

0 |

117 (188) |

— |

5,134 (8,262) |

3.5 (5.6) |

| Mercury-Redstone 4 |

Liberty Bell 7 |

Grissom |

12:20 on July 21, 1961 |

Launch Complex-5 |

15 m 37 s |

0 |

118 (190) |

— |

5,168 (8,317) |

5.8 (9.3) |

| Mercury-Atlas 6 |

Friendship 7 |

Glenn |

14:47 on February 20, 1962 |

Launch Complex-14 |

4 h 55 m 23 s |

3 |

162 (261) |

100 (161) |

17,544 (28,234) |

46 (74) |

| Mercury-Atlas 7 |

Aurora 7 |

Carpenter |

12:45 on May 24, 1962 |

Launch Complex-14 |

4 h 56 m 5 s |

3 |

167 (269) |

100 (161) |

17,549 (28,242) |

248 (400) |

| Mercury-Atlas 8 |

Sigma 7 |

Schirra |

12:15 on October 3, 1962 |

Launch Complex-14 |

9 h 13 m 15 s |

6 |

176 (283) |

100 (161) |

17,558 (28,257) |

4.6 (7.4) |

| Mercury-Atlas 9 |

Faith 7 |

Cooper |

13:04 on May 15, 1963 |

Launch Complex-14 |

1 d 10 h 19 m 49 s |

22 |

166 (267) |

100 (161) |

17,547 (28,239) |

5.0 (8.1) |

-

Shepard’s flight watched on TV in the White House. May 1961.

-

John Glenn honored by the President. February 1962.

-

USS Kearsarge with crew spelling Mercury-9. May 1963.

Unmanned[edit]

The 20 unmanned flights used Little Joe, Redstone, and Atlas launch vehicles.[132] They were used to develop the launch vehicles, launch escape system, spacecraft and tracking network.[208] One flight of a Scout rocket attempted to launch an unmanned satellite for testing the ground tracking network, but failed to reach orbit. The Little Joe program used seven airframes for eight flights, of which three were successful. The second Little Joe flight was named Little Joe 6, because it was inserted into the program after the first 5 airframes had been allocated.

| Purpose |

| Little Joe 1 |

August 21, 1959 |

20 s |

Test of launch escape system during flight. |

Failure |

| Big Joe 1 |

September 9, 1959 |

13 m 00 s |

Test of heat shield and Atlas/spacecraft interface. |

Partly success |

| Little Joe 6 |

October 4, 1959 |

5 m 10 s |

Test of spacecraft aerodynamics and integrity. |

Partly success |

| Little Joe 1A |

November 4, 1959 |

8 m 11 s |

Test of launch escape system during flight with boiler plate capsule. |

Partly success |

| Little Joe 2 |

December 4, 1959 |

11 m 6 s |

Escape system test with primate at high altitude. |

Success |

| Little Joe 1B |

January 21, 1960 |

8 m 35 s |

Maximum-q abort and escape test with primate with boiler plate capsule. |

Success |

| Beach Abort |

May 9, 1960 |

1 m 31 s |

Test of the off-the-pad abort system. |

Success |

| Mercury-Atlas 1 |

July 29, 1960 |

3 m 18 s |

Test of spacecraft / Atlas combination. |

Failure |

| Little Joe 5 |

November 8, 1960 |

2 m 22 s |

First test of escape system with a production spacecraft. |

Failure |

| Mercury-Redstone 1 |

November 21, 1960 |

2 s |

Test of production spacecraft at max-q. |

Failure |

| Mercury-Redstone 1A |

December 19, 1960 |

15 m 45 s |

Qualification of spacecraft / Redstone combination. |

Success |

| Mercury-Redstone 2 |

January 31, 1961 |

16 m 39 s |

Qualification of spacecraft with chimpanzee. |

Success |

| Mercury-Atlas 2 |

February 21, 1961 |

17 m 56 s |

Qualified Mercury/Atlas interface. |

Success |

| Little Joe 5A |

March 18, 1961 |

23 m 48 s |

Second test of escape system with a production Mercury spacecraft. |

Partly success |

| Mercury-Redstone BD |

March 24, 1961 |

8 m 23 s |

Final Redstone test flight. |

Success |

| Mercury-Atlas 3 |

April 25, 1961 |

7 m 19 s |

Orbital flight with robot astronaut.[226][n 33] |

Failure |

| Little Joe 5B |

April 28, 1961 |

5 m 25 s |

Third test of escape system with a production spacecraft. |

Success |

| Mercury-Atlas 4 |

September 13, 1961 |

1 h 49 m 20 s |

Test of environmental control system with robot astronaut in orbit. |

Success |

| Mercury-Scout 1 |

November 1, 1961 |

44 s |

Test of Mercury tracking network. |

Failure |

| Mercury-Atlas 5 |

November 29, 1961 |

3 h 20 m 59 s |

Test of environmental control system in orbit with chimpanzee. |

Success |

After suborbital manned flights

-

Little Joe 1B at launch with Miss Sam, 1960

-

Mercury-Redstone 1: launch escape system lift-off after 4” launch, 1960

-

Mercury-Redstone 2: Ham, 1961

-

Mercury-Atlas 5: Enos, 1961

Canceled[edit]

Nine of the planned flights were cancelled. Suborbital flights were planned for four other astronauts but the number of flights was cut down gradually and finally all remaining were cancelled after Titov’s flight.[256][n 37] Mercury-Atlas 9 was intended to be followed by more one-day flights and even a three-day flight but with the coming of the Gemini Project it seemed unnecessary. The Jupiter booster was, as mentioned above, intended to be used for different purposes.

| Mission |

Pilot |

Planned Launch |

Cancellation |

| Mercury-Jupiter 1 |

|

|

July 1, 1959 |

| Mercury-Jupiter 2 |

Chimpanzee |

First Quarter, 1960 |

July 1, 1959[n 38] |

| Mercury-Redstone 5 |

Glenn (likely) |

March 1960 |

August 1961 |

| Mercury-Redstone 6 |

|

April 1960 |

July 1961 |

| Mercury-Redstone 7 |

|

May 1960 |

|

| Mercury-Redstone 8 |

|

June 1960 |

|

| Mercury-Atlas 10 |

Shepard |

October 1963 |

June 13, 1963[n 39] |

| Mercury-Atlas 11 |

Grissom |

Fourth Quarter, 1963 |

October 1962[264] |

| Mercury-Atlas 12 |

Schirra |

Fourth Quarter, 1963 |

October 1962[265] |

Impact and legacy[edit]

The project was delayed by 22 months, counting from the beginning until the first orbital mission.[193] It had a dozen prime contractors, 75 major subcontractors, and about 7200 third-tier subcontractors, who together employed two million people.[193] An estimate of its cost made by NASA in 1969 gave $392.6 million ($1.74 billion adjusted for inflation), broken down as follows: Spacecraft: $135.3 million, launch vehicles: $82.9 million, operations: $49.3 million, tracking operations and equipment: $71.9 million and facilities: $53.2 million.[267]

Today the Mercury program is commemorated as the first manned American space program. It did not win the race against the Soviet Union, but gave back national prestige and was scientifically a successful precursor of later programs such as Gemini, Apollo and Skylab.[n 40] During the 1950s, some experts doubted that manned spaceflight was possible.[n 41] Still when John F. Kennedy was elected president, many including he had doubts about the project.[272] As president he chose to support the programs a few months before the launch of Freedom 7,[273] which became a great public success.[274][n 42] Afterwards, a majority of the American public supported manned spaceflight, and within a few weeks, Kennedy announced a plan for a manned mission to land on the Moon and return safely to Earth before the end of the 1960s.[278] The six astronauts who flew were awarded medals,[279] driven in parades and two of them were invited to address a joint session of the U.S. Congress.[280] As a response to the selection criteria, which ruled out women, a private project was founded in which 13 women pilots successfully underwent the same tests as the men in Project Mercury. It was named Mercury 13 by the media[n 43]Despite this effort, NASA did not select female astronauts until 1978 for the Space Shuttle.

In 1964, a monument commemorating Project Mercury was unveiled near Launch Complex 14 at Cape Canaveral, featuring a metal logo combining the symbol of Mercury with the number 7.[284] In 1962, the United States Postal Service honored the Mercury-Atlas 6 flight with a Project Mercury commemorative stamp, the first U.S. postal issue to depict a manned spacecraft.[285][n 44] On film, the program was portrayed in The Right Stuff a 1983 adaptation of Tom Wolfe‘s 1979 book of the same name.[287] On February 25, 2011, the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, the world’s largest technical professional society, awarded Boeing (the successor company to McDonnell Aircraft) a Milestone Award for important inventions which debuted on the Mercury spacecraft.[288][n 45]

-

Mercury monument at Launch Complex 14, 1964

-

Displays[edit]

The spacecraft that flew, together with some that did not are on display in the United States. Friendship 7 (capsule No. 13) went on a global tour, popularly known as its “fourth orbit”. [289]

Patches[edit]

Commemorative patches were designed by entrepreneurs after the Mercury program to satisfy collectors.[290][n 47]

-

John Glenn documentary from 50th Anniversary of Friendship 7, 2012.

Graphics[edit]

Astronauts assignments[edit]

-

Mercury 7 astronaut assignments. Schirra had the most flights with three; Glenn, though being the first to leave NASA, had the last with a Space Shuttle mission in 1998.[291] Shepard was the only one to walk on the Moon.

Tracking network[edit]

-

Ground track and tracking stations for Mercury-Atlas 8. Spacecraft starts from Cape Canaveral in Florida and moves east; each new orbit-track is displaced to the left due to the rotation of the Earth. It moves between latitudes 32.5° north and 32.5° south. Key: 1–6: orbit number. Yellow: launch. Black dot: tracking station. Red: range of station; Blue: landing.

Spacecraft cutaway[edit]

-

-

The three axes of rotation for the spacecraft: yaw, pitch and roll

Control panels and handle[edit]

-

The control panels of Friendship 7. The panels changed between flights, among others the periscope screen that dominates the center of these panels was dropped for the final flight.

-

3-axis handle for attitude control

Launch complex[edit]

-

Launch Complex 14 just before launch (service tower rolled aside). Preparations for launch were made at blockhouse.

Earth landing system tests[edit]

-

Drop of boilerplate spacecraft in training of landing and recovery. 56 such qualification tests were made together with tests of individual steps of the system.

Space program comparison[edit]

-

NASA illustration comparing boosters and spacecraft from Apollo (biggest), Gemini and Mercury (smallest).

The Pronk Pops Show 810, December 8, 2016, Story 1: Astronaut and Senator John Glenn Dies At 95 — The Right Stuff — Godspeed, John Glenn — Videos

Posted on December 8, 2016. Filed under: American History, Blogroll, Books, Breaking News, College, Communications, Computers, Congress, Countries, Defense Spending, Education, Government Spending, History, Human, Investments, John Glenn, Life, Media, News, Nuclear Weapons, Philosophy, Photos, Politics, Radio, Raymond Thomas Pronk, Senate, Space, Space Flights, Transportation, U.S. Space Program, United States of America, Videos, Violence, War, Wealth, Wisdom | Tags: 8 December 2016, Air Medal, America, American Hero, American Icon, An Evening With Two Mercury Astronauts, Articles, Astronaut, Audio, Book, Breaking News, Broadcasting, Capitalism, Cartoons, Charity, Citizenship, Clarity, Classical Liberalism, Collectivism, Commentary, Commitment, Communicate, Communication, Concise, Congressional Gold Medal, Convincing, Courage, Culture, Current Affairs, Current Events, Decorated Marine Pilot, Discovery 7, Distinguished Flying Cross(6), Economic Growth, Economic Policy, Economics, Education, Evil, Experience, Faith, Family, First, Fiscal Policy, Free Enterprise, Freedom, Freedom of Speech, Friends, Give It A Listen!, God, Godspeed, Godspeed John Glenn, Good, Goodwill, Growth, Hope, Individualism, John Glenn, Knowledge, Korean War, Liberty, Life, Love, Lovers of Liberty, Monetary Policy, Movie, MPEG3, NASA, NASA FRIENDSHIP 7 PROJECT MERCURY, News, Opinions, Peace, Photos, Podcasts, Political Philosophy, Politics, President John F. Kennedy, Presidential Medal of Freedom, Project Mercury, Prosperity, Radio, Raymond Thomas Pronk, Representative Republic, Republic, Resources, Respect, Rule of Law, Rule of Men, Senator, Senator John Glenn, Show Notes, Space Program, Space Shuttle Program, Talk Radio, Test Pilot, Test Pilots, The Pronk Pops Show, The Pronk Pops Show 810, The Right Stuff, Tom Wolf, Truth, Tyranny, U.S. Constitution, United States of America, Videos, Virtue, War, Wisdom, World War II |

The Pronk Pops Show Podcasts

Pronk Pops Show 810: December 8, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 809: December 7, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 808: December 6, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 807: December 5, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 806: December 2, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 805: December 1, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 804: November 30, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 803: November 29, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 802: November 28, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 801: November 22, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 800: November 21, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 799: November 18, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 798: November 17, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 797: November 16, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 796: November 15, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 795: November 14, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 794: November 10, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 793: November 9, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 792: November 8, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 791: November 7, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 790: November 4, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 789: November 3, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 788: November 2, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 787: October 31, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 786: October 28, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 785: October 27, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 784: October 26, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 783: October 25, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 782: October 24, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 781: October 21, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 780: October 20, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 779: October 19, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 778: October 18, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 777: October 17, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 776: October 14, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 775: October 13, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 774: October 12, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 773: October 11, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 772: October 10, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 771: October 7, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 770: October 6, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 769: October 5, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 768: October 3, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 767: September 30, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 766: September 29, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 765: September 28, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 764: September 27, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 763: September 26, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 762: September 23, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 761: September 22, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 760: September 21, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 759: September 20, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 758: September 19, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 757: September 16, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 756: September 15, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 755: September 14, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 754: September 13, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 753: September 12, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 752: September 9, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 751: September 8, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 750: September 7, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 749: September 2, 2016

Pronk Pops Show 748: September 1, 2016

Story 1: Astronaut and Senator John Glenn Dies At 95 — The Right Stuff — Godspeed, John Glenn — Videos

Remembering John Glenn, space pioneer and American statesman

John Glenn Dead at 95 | Remembering the First American To Orbit Earth

Looking back at John Glenn’s history-making life

Former astronaut John Glenn dead at 95

Astronaut and Sen. John Glenn Dead at 95

John Glenn & President John F. Kennedy

The John Glenn Story (1963)

Senator John Glenn – Biography

THE JOHN GLENN STORY NASA FRIENDSHIP 7 PROJECT MERCURY 45404

First American in Orbit: John Glenn “Friendship 7” Project Mercury 1962 NASA

Project Mercury Summation 1963 NASA; First American Astronauts in Orbit

NASA Project Mercury: 1960’s Manned Spaceflight / Space Documentary S88TV1

Friendship 7 & Astronaut John Glenn – 1962 NASA Educational Documentary – WDTVLIVE42

John Glenn tells the story of Friendship 7

History in the First Person: Building the Mercury Capsule

Flying Mercury-Atlas 6 In Honor Of John Glenn

John Glenn: Earning the Right Stuff as a Decorated Marine Aviator and Navy Test Pilot

Longest Project Mercury Spaceflight: Flight of Faith 7 1963 NASA; MA-9; Gordon Cooper

The Real ‘Right stuff’

Great Books – The Right Stuff [TLC Documantary]

The Right Stuff Theme • Bill Conti

From the 1983 Phillip Kaufman film “The Right Stuff” with Sam Shepard, Scott Glenn, Ed Harris & Dennis Quaid. The film tells the story of the Mercury Seven Astronauts.

Chuck Yeager breaks The Sound Barrier (from THE RIGHT STUFF)

The Right Stuff (edited last scene) – Absolutely Awe-Inspiring !!

Mercury Capsule Without a Window

The Right Stuff – Glenn’s Launch Aborted

The Right Stuff. Godspeed Ed Harris – I mean, John Glenn.

The Right Stuff – The Bell X-1 (with Levon Helm as CPT Jack Ridley)

The Right Stuff (Part 2)

The Right Stuff (Part 3)

The Right Stuff (Part 4)

The Right Stuff (Part 5)

The Right Stuff (Part 6)

The Right Stuff (Part 7)

Annie Glenn: An amazing life

Mercury Space Project: ” The Astronauts”, the Real Right Stuff, training and development (1960)

Mercury astronaut launch in “The Right stuff” movie cut, 1983

Eighty-Nine Year Old Chuck Yeager • F-15 Eagle Honor Flight

An Evening With Two Mercury Astronauts

Godspeed, John Glenn

John Glenn, American hero, aviation icon and former U.S. senator, dies at 95

By Joe Hallett

The Columbus Dispatch • Thursday December 8, 2016 5:35 PM

His legend is otherworldly and now, at age 95, so is John Glenn.

An authentic hero and genuine American icon, Glenn died this afternoon surrounded by family at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus after a remarkably healthy life spent almost from the cradle with Annie, his beloved wife of 73 years, who survives.

He, along with fellow aviators Orville and Wilbur Wright and moon-walker Neil Armstrong, truly made Ohio first in flight.

“John Glenn is, and always will be, Ohio’s ultimate hometown hero, and his passing today is an occasion for all of us to grieve,” said Ohio Gov. John R. Kasich. “As we bow our heads and share our grief with his beloved wife, Annie, we must also turn to the skies, to salute his remarkable journeys and his long years of service to our state and nation.

“Though he soared deep into space and to the heights of Capitol Hill, his heart never strayed from his steadfast Ohio roots. Godspeed, John Glenn!” Kasich said.

For more on John Glenn’s life, visit Dispatch.com/JohnGlenn

Glenn’s body will lie in state at the Ohio Statehouse for a day, and a public memorial service will be held at Ohio State University’s Mershon Auditorium. He will be buried near Washington, D.C., at Arlington National Cemetery in a private service. Dates and times for the public events will be announced soon.

Glenn lived a Ripley’s Believe It or Not! life. As a Marine Corps pilot, he broke the transcontinental flight speed record before being the first American to orbit the Earth in 1962 and, 36 years later at age 77 in 1998, becoming the oldest man in space as a member of the seven-astronaut crew of the shuttle Discovery.

He made that flight in his 24th and final year in the U.S. Senate, from whence he launched a short-lived bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984. Along the way, Glenn became moderately wealthy from an early investment in Holiday Inns near Disney World and a stint as president of Royal Crown International.

In one of his last public appearances, Glenn, with Annie by his side, sat in the Port Columbus airport terminal on June 28 as officials renamed it in his honor — the John Glenn Columbus International Airport.

In addition to his world-famous career in aviation and aerospace, Glenn had a relationship with that particular airport that is likely second to none. Glenn, who turned 8 the month that Port Columbus opened in July 1929, recalled asking his parents to stop at the airport so he could watch the planes come and go while he was growing up in New Concord, 70 miles east of Columbus.

Glenn recalled “many teary departures and reunions” at the airport’s original terminal on Fifth Avenue during his time as a military aviator during World War II. He and his wife Annie, who had been married 73 years, later kept a small Beechcraft plane at Lane Aviation on the airport grounds for many years, and he only gave up flying his own plane at age 90.

Privately, this man who had been honored by presidents and immortalized in history books and movies, told friends that for an aviator, seeing his name on the Columbus airport was the highest honor he could imagine.

Glenn, who lived with Annie for the past decade in a Downtown Columbus condo, dedicated his life to public service, devoting many of his later years to Ohio State University, which in 2005 converted the century-old Page Hall into the John Glenn Institute for Public Service and Public Policy and the School of Public Policy and Management. It is now the John Glenn College of Public Affairs.

“He was very proud of the Glenn College,” said Jack Kessler, chairman of the New Albany Company, a former Ohio State trustee and longtime friend of the Glenns. “It’s a legacy that will carry on his mission toward good public policy.”

While Glenn held office as a Democrat, he wasn’t partisan, Kessler said. “I never heard him say a bad thing about anyone. Some of his best friends were Republicans, and he could work with anyone.”

Surrounded by dozens of students striving to earn master’s and doctoral degrees from the institute, Glenn said at its dedication, “If we inspire a few young people into careers of public service and politics, this will all be worth it.”

Remarkably physically fit and energetic, Glenn only began encountering health problems in 2013 when he had a pacemaker implanted and missed some public appearances due to vertigo.

In 2011, he and Annie both had knee-replacement surgery, which kept them from repeating a planned road trip like the impromptu 8,400-mile journey throughout the West they took a year earlier in their Cadillac when she was 89 and he 88.

Raised in New Concord, where he and Annie both went to Muskingum College, Glenn aspired to be a medical doctor, but World War II sidetracked that ambition and launched a life of uncommon achievement and bravery. At age 8, he took his first ride in an open-cockpit airplane and ended up virtually living life in the sky, continuing to fly until 2011 when he put up for sale the twin-engine Beech Baron he had owned since 1981.

“I miss it,” Glenn told The Dispatch in 2012 “I never got tired of flying.”

Glenn flew 149 combat missions in World War II and Korea, where his wingman and eventual lifelong friend was baseball legend Ted Williams. In Korea, Glenn earned the nickname “Old Magnet Ass” due to his skill in landing his airplane under any condition, even after it was riddled with bullets and had blown tires.

Born not far from New Concord in Cambridge on July 18, 1921, Glenn and his parents moved about 10 miles west in 1923 to New Concord. His father was a plumber and his mother a teacher who joined a social group called the Twice 5 Club, which got together once a month. Another couple in the club had a daughter, Annie Castor, who was a year older than Glenn, and the two toddlers often shared a playpen while their parents played cards.

Their relationship evolved into a quintessential American love story, with the spark between them first igniting when they were in junior high school.

“To write a story about either of them, if it doesn’t include the other, then it just isn’t complete,” their daughter, Lyn, told The Dispatch in 2007. She and her brother, David, a California doctor, survive.

John and Annie were married on April 6, 1943, and the next January, as they held each other searching for something to say as he prepared to ship out for combat in the South Pacific, John said, “I’m just going down to the corner store to get a pack of gum.”

From that day on, she kept a gum wrapper in her purse.

To many with disabilities, Annie became a heroine in her own right as she struggled to conquer near-debilitating stuttering.

For more than half of her life, she counted on others to speak for her, publicly uncommunicative in a world that demanded more from her as her husband’s fame ascended.

Through it all, John stood by Annie, who, in 1973, underwent an innovative treatment regimen that dramatically improved her speech to the extent that she was delivering speeches on behalf of her husband’s 1984 presidential candidacy.

Glenn, who received his pilot’s license in 1941, was at home in the sky, soon evident after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and he left Muskingum College to enlist in the Marine Air Corps. In the Pacific, he flew 59 missions over the Marshall Islands.

After being stationed in China and Guam when World War II ended, Glenn was a flight instructor in Texas before being transferred to Virginia. When the Korean War broke out, Glenn applied for combat duty, and flew 90 missions. Overall, he received the Distinguished Flying Cross six times and was awarded the Air Medal with 18 clusters.

After returning from Korea, Glenn became a test pilot. He set a coast-to-coast speed record in 1957, piloting a Navy jet fighter from California to New York in 3 hours and 23 minutes. In 1959, he was selected as one of the country’s first seven astronauts, a historic group immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s 1979 book The Right Stuff, the basis for a movie of the same name.

The United States was enveloped in a cold war with the Soviet Union, and after a series of U.S. rockets had blown up, the American psyche was dealt a blow in 1961 when Russian Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space and the first to orbit Earth.

The third American in space after suborbital missions by Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom, Glenn finally equaled Gagarin’s achievement by blasting off on Feb. 20, 1962, after weather and mechanical problems caused his mission to be postponed 10 times.

Crammed into the 7-foot-wide Friendship 7 space capsule atop a 100-foot-tall Atlas rocket loaded with 250,000 pounds of explosive fuel, Glenn launched 160-miles into space, orbiting the world three times at 17,500 miles per hour.

Reflecting many years later, Glenn would say that computers were the greatest technological achievement during his life, but there were none on Friendship 7, and deep into the flight he had to take manual control of the capsule when systems malfunctioned.

As the capsule descended for a watery landing, mission control feared that its heat shield was peeling off. Well past four hours into the flight, Glenn was told of the problem and knew he could be burned alive in an instant (Annie was notified to expect the worst), but the astronaut stayed focused even as fiery pieces of his spacecraft flew by his window.

“You didn’t really have time to think about it,” he told students at COSI Columbus 45 years later. “Long before you actually got to the flight itself, you sort of made peace with mortality.”

Safely splashing in the Atlantic Ocean 800 miles southeast of Bermuda, Glenn’s historic flight invigorated the nation and catapulted him into American lore. He addressed a joint session of Congress and rode in a convertible with Annie as 4 million people cheered him in a Manhattan ticker-tape parade.

In 2007, 45 years after his historic orbital mission, Glenn told a Columbus audience how much he longed to return to space right away, only to learn years after leaving the space program that President John F. Kennedy, fearing the worst, secretly had barred him from other flights to spare the country the potential loss of a national hero.

Glenn admitted in that speech that he was jealous in 1969 when fellow Ohioan Armstrong became the first human to set foot on the moon.

In 1964, only two years after his famous flight on Friendship 7, Glenn ran in the Democratic Senate primary against incumbent Sen. Stephen M. Young. But only six weeks after announcing his candidacy, Glenn dropped out of the race after damaging his inner ear in a bathroom fall, an injury that caused severe dizziness and balance problems. He recovered eight months later.

Glenn ran for the Senate again in 1970, but lost in the primary to Howard M. Metzenbaum, whom he defeated in a rematch four years later. He handily won election that fall over Cleveland Mayor Ralph Perk and won re-election by huge margins in 1980 and 1986.

After winning re-election in 1980 by the largest margin in Ohio history, Glenn ran for president in 1984. He was seen as the leading challenger to former Vice President Walter F. Mondale for the Democratic nomination, and was the candidate many considered to have the best chance of defeating President Ronald Reagan in the general election.

But plagued by a disorganized campaign and with a centrist theme ill-suited to a liberal-dominated Democratic primary process, Glenn finished back in the pack in the important Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary. He borrowed $2 million to compete in the Southern primaries, but he didn’t win a state and dropped out of the race.

The debt remaining from that race, which rose to more than $3 million, became a campaign issue for Glenn in subsequent Senate races and nagged him until 2006 when the Federal Elections Commission finally allowed him to close the books on it after years of chipping away.

The third term of his four in the Senate was dominated by a Senate investigation into allegations that he improperly interceded with S&L regulators on behalf of Charles Keating, who had raised or donated $242,000 to Glenn’s political committees. Glenn personally spent more than $500,000 to defend his honor, and the Senate Ethics Committee cleared him of wrongdoing.

“I spend half a million dollars on my defense, and I wouldn’t pull back a penny of it,” Glenn said then. “The reason I felt so strongly about it was that it involved my honor, and if I had to sell everything I had and mortgaged the house, I would have done everything I could to see the truth come out.”

In his final year as a U.S. senator in 1998, Glenn was reborn as an astronaut. At 77, he orbited the Earth with six astronauts aboard shuttle Discovery, once again rendering his body and mind to the study of science, providing insight into how the oldest man ever launched into space held up. Glenn, remarkably fit, became an inspiration once again to mankind.

The events of John Glenn’s life, and his footprint on history, are chronicled in countless books and beyond. The Friendship 7 capsule is in the Smithsonian, his papers and memorabilia are archived at Ohio State, and his life with Annie — and much more — are displayed at the Glenn Historic Site in New Concord.

Joe Hallett is a retired reporter and senior editor of The Dispatch.

http://www.dispatch.com/content/stories/local/2016/12/john-glenn/john-glenn.html

John Glenn

January 3, 1987 – January 3, 1995

from Ohio

December 24, 1974 – January 3, 1999

July 18, 1921

Cambridge, Ohio, U.S.

Columbus, Ohio, U.S.

University of Maryland, College Park

Presidential Medal of Freedom

Congressional Space Medal of Honor

NASA Distinguished Service Medal

VMF-155

VMF-218

VMA-311

51st Fighter Wing

Korean War

John Herschel Glenn Jr. (July 18, 1921 – December 8, 2016) was an American aviator, engineer, astronaut, and United States Senator from Ohio. In 1962 he became the first American to orbit the Earth, circling three times. Before joining NASA, he was a distinguished fighter pilot in both World War II and Korea, with five Distinguished Flying Crosses and eighteen clusters.

Glenn was one of the “Mercury Seven” group of military test pilots selected in 1959 by NASA to become America’s first astronauts. On February 20, 1962, he flew the Friendship 7 mission and became the first American to orbit the Earth and the fifth person in space. Glenn received the Congressional Space Medal of Honor in 1978, was inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame in 1990, and was the last surviving member of the Mercury Seven.

After he resigned from NASA in 1964, Glenn planned to run for a U.S. Senate seat from Ohio. A member of the Democratic Party, he first won election to the Senate in 1974 where he served through January 3, 1999.

He retired from the Marine Corps in 1965, after twenty-three years in the military, with over fifteen medals and awards, including the NASA Distinguished Service Medal and the Congressional Space Medal of Honor. In 1998, while still a sitting senator, he became the oldest person to fly in space, and the only one to fly in both the Mercury and Space Shuttle programs as crew member of the Discovery space shuttle. He was also awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012.

Contents

[hide]

Early life, education and military service

Glenn’s childhood home in New Concord

John Glenn was born on July 18, 1921, in Cambridge, Ohio, the son of John Herschel Glenn, Sr. (1895–1966) and Clara Teresa (née Sproat) Glenn (1897–1971).[1][2] He was raised in nearby New Concord.[3]

After graduating from New Concord High School in 1939, he studied Engineering at Muskingum College. He earned a private pilot license for credit in a physics course in 1941.[4] Glenn did not complete his senior year in residence or take a proficiency exam, both requirements of the school for the Bachelor of Science degree. However, the school granted Glenn his degree in 1962, after his Mercury space flight.[5]

World War II

Military portrait of John Glenn

When the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II, Glenn quit college to enlist in the U.S. Army Air Corps. However, he was never called to duty, and in March 1942 enlisted as a United States Navy aviation cadet. He went to the University of Iowa for preflight training, then continued on to NAS Olathe, Kansas, for primary training. He made his first solo flight in a military aircraft there. During his advanced training at the NAS Corpus Christi, he was offered the chance to transfer to the U.S. Marine Corps and took it.[6]

Upon completing his training in 1943, Glenn was assigned to Marine Squadron VMJ-353, flying R4D transport planes. He transferred to VMF-155 as an F4U Corsair fighter pilot, and flew 59 combat missions in the South Pacific.[7] He saw combat over the Marshall Islands, where he attacked anti-aircraft batteries on Maloelap Atoll. In 1945, he was assigned to NAS Patuxent River, Maryland, and was promoted to captain shortly before the war’s end.[3]:35

Glenn flew patrol missions in North China with the VMF-218 Marine Fighter Squadron, until it was transferred to Guam. In 1948 he became a flight instructor at NAS Corpus Christi, Texas, followed by attending the Amphibious Warfare School.[8]:34

Korean War

Glenn’s USAF F-86F that he dubbed “MiG Mad Marine” during the Korean War, 1953

During the Korean War, Glenn was assigned to VMF-311, flying the new F9F Panther jet interceptor. He flew his Panther in 63 combat missions, gaining the nickname “magnet ass” from his alleged ability to attract enemy flak.[9] On two occasions, he returned to his base with over 250 holes in his aircraft.[10] For a time, he flew with Marine reservist Ted Williams, a future Hall of Fame baseball player for the Boston Red Sox, as his wingman. He also flew with future Major General Ralph H. Spanjer.[11]

Glenn flew a second Korean combat tour in an interservice exchange program with the United States Air Force, 51st Fighter Wing. He logged 27 missions in the faster F-86F Sabre and shot down three MiG-15s near the Yalu River in the final days before the ceasefire.[9]

For his service in 149 combat missions in two wars, he received numerous honors, including the Distinguished Flying Cross (six occasions) and the Air Medal with eighteen award stars.[12]

Test pilot

Glenn returned to NAS Patuxent River, appointed to the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School (class 12), graduating in 1954.[13] He served as an armament officer, flying planes to high altitude and testing their cannons and machine guns.[14] He was assigned to the Fighter Design Branch of the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics (now Bureau of Naval Weapons) as a test pilot on Navy and Marine Corps jet fighters in Washington, D.C., from November 1956 to April 1959, during which time he also attended the University of Maryland.[15]

Glenn had nearly 9,000 hours of flying time, with approximately 3,000 hours in jet aircraft.[15]

On July 16, 1957, Glenn completed the first supersonic transcontinental flight in a Vought F8U-3P Crusader.[16] The flight from NAS Los Alamitos, California, to Floyd Bennett Field, New York, took 3 hours, 23 minutes and 8.3 seconds. As he passed over his hometown, a child in the neighborhood reportedly ran to the Glenn house shouting “Johnny dropped a bomb! Johnny dropped a bomb! Johnny dropped a bomb!” as the sonic boom shook the town.[17] Project Bullet, the name of the mission, included both the first transcontinental flight to average supersonic speed (despite three in-flight refuelings during which speeds dropped below 300 mph), and the first continuous transcontinental panoramic photograph of the United States. For this mission Glenn received his fifth Distinguished Flying Cross.[18]

NASA career

John Glenn in his Mercury spacesuit

While Glenn was on duty at Patuxent and Washington, Glenn began to read everything he could about space. His office was requested to furnish a test pilot to be sent to the Langley Air Force Base in Virginia to make some runs on a spaceflight simulator, which was a part of NASA research on reentry vehicle shapes. The officer would also be sent to the Naval Air Development Center in Johnsville, Pennsylvania. The test pilot would be subjected to high g-forces in a centrifuge to compare to the data collected in the simulator. Glenn requested this position and was granted it. He spent a few days at Langley and a week in Johnsville for the testing.[19]